The confidence gap isn’t the problem. Culture is.

.avif)

%20(1).png)

Picture a meeting that ends with the usual ritual.

“Any wins to share before we wrap?”

A pause. A few polite smiles. Someone mentions a project milestone in a way that sounds like an apology. Someone else says nothing, even though their work quietly saved a project.

It’s tempting to diagnose this as a confidence issue. We tell people to “own their accomplishments,” to “speak up,” to “build a personal brand.” We assume the barrier lives inside the individual.

But our latest research suggests we’ve been looking in the wrong place.

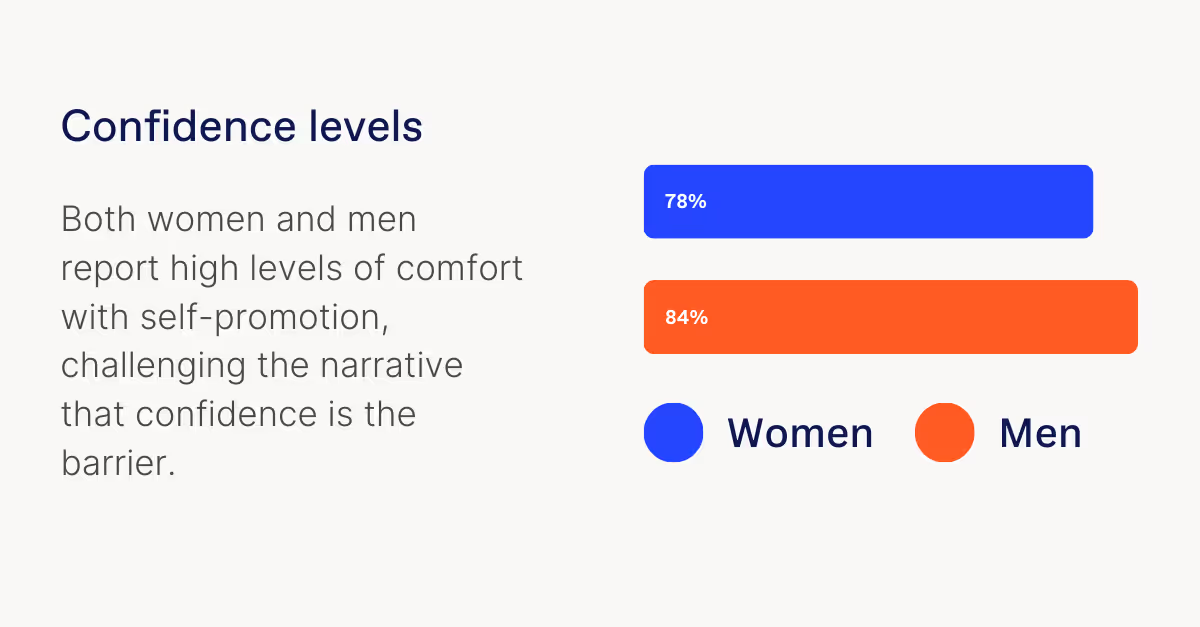

In a survey of 259 managers and business leaders across the U.S. and Canada (conducted by Centiment on Workleap’s behalf in April 2025), most employees aren’t shrinking violets. They’re actually pretty comfortable with self-promotion: 78% of women and 84% of men say they’re at least somewhat comfortable promoting their professional achievements.

That’s not a confidence deficit. That’s a culture problem wearing confidence’s costume.

Because the real question isn’t, “Are people comfortable sharing wins?”

It’s, “Do they believe it’s safe?”

When self-promotion becomes a risk assessment

In workplaces, self-promotion is rarely just self-promotion. It’s a signal. And in some cultures, signals come with consequences.

Our data shows that women, in particular, are doing a more complex calculation before they speak.

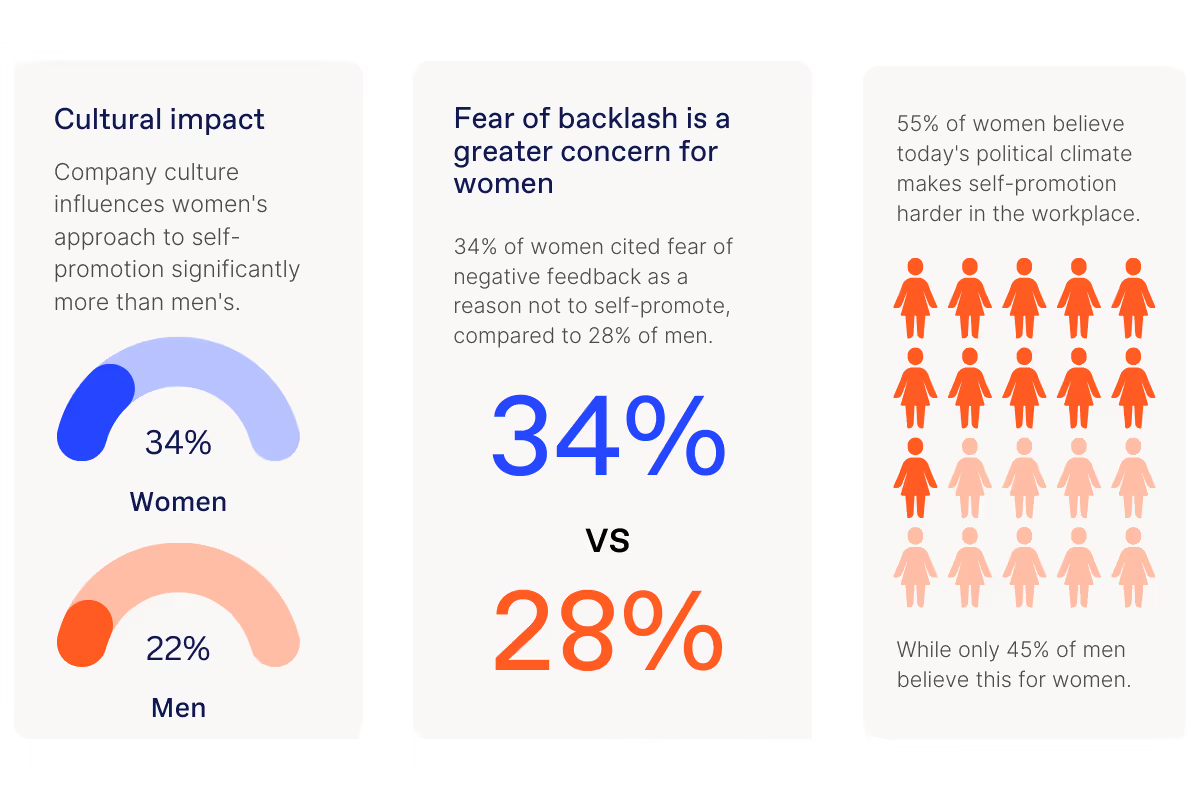

- Company culture has more gravitational pull for women. 34% of women say workplace culture influences how they approach self-promotion, compared to 22% of men.

- Backlash is a bigger concern. 34% of women cite fear of negative feedback as a reason not to self-promote (vs. 28% of men).

- The broader political environment adds pressure. 55% of women say today’s political climate makes self-promotion harder—while only 45% of men believe this is true for women.

Read that last one again. It’s not just that women feel the pressure more; it’s that men are less likely to perceive how heavy that pressure is.

This is how culture stalls recognition: not by erasing ambition, but by making expression feel risky.

And when expressing your work feels like stepping onto a social minefield, you don’t stop caring about your career. You just stop volunteering evidence.

The overlooked lever: social permission

Here’s the most telling part of the survey, and it has nothing to do with charisma.

When we asked what most shapes how people promote their achievements, encouragement from managers and peers ranked nearly as high as confidence itself:

- Encouragement from managers and peers: 45% of women, 46% of men

- Confidence: 50% of women, 55% of men

That’s the headline hiding in the middle of the data: self-promotion isn’t simply a personal trait. It’s a behavior people adopt when the environment gives them permission.

In other words: culture doesn’t just “influence” recognition. Culture decides who gets to speak without consequences.

Why public conversations change private behavior

Workplaces don’t exist in a vacuum. People bring the outside world into the office—sometimes literally, via Slack, LinkedIn, and the headlines they read before their first coffee.

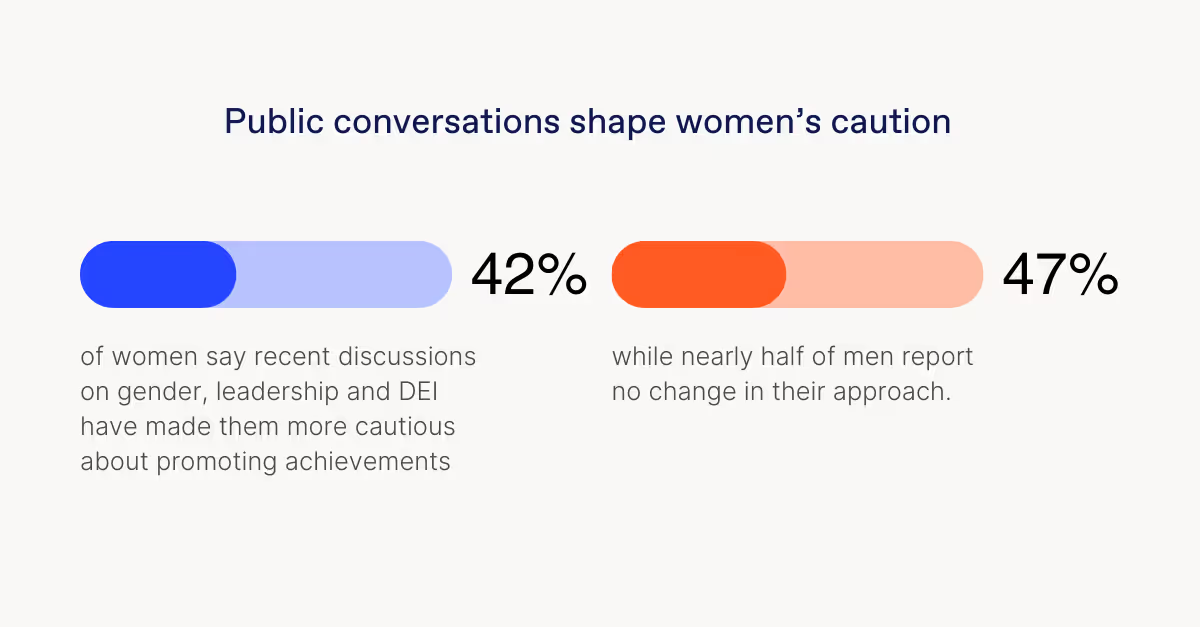

The survey found that 42% of women say recent conversations about gender, leadership, and DEI have made them more cautious about promoting their achievements. Nearly half of men (47%) say those conversations didn’t change their approach.

This isn’t about whether those conversations are “good” or “bad.” It’s about what they do to the perceived risk of being visible.

If you believe visibility increases scrutiny—and scrutiny increases penalties—you start to treat self-promotion like a high-stakes move.

Not because you don’t believe in your achievements.

Because you do.

Age makes the story more nuanced

There’s another wrinkle that complicates the “confidence” narrative: age.

Younger women are more at ease with self-promotion: 52% of women aged 25–44 say they feel very comfortable, compared to 30% of women aged 45–64.

This could mean many things. It could reflect changing norms. It could reflect the confidence that comes from growing up in an era where visibility is part of work. Or it could reflect something more sobering: that over time, people learn which behaviors get rewarded—and which get punished.

Culture teaches. People adapt.

Where people feel safe to speak up

If you want a clue about what employees trust, look at where they choose to share wins.

Across demographics, the most comfortable channels are still face-to-face conversations with peers and managers, with LinkedIn as the top digital option.

That makes sense. In-person communication provides context: tone, rapport, social cues. It lets people test how their message lands. Digital channels can flatten nuance—and in a culture where backlash is a concern, nuance matters.

Platform preferences also tell a story about credibility and risk:

- Men are more likely to use X/Twitter (35% vs. 21%) and leverage more platforms overall.

- Women lean more toward industry conferences (26%), a space that tends to offer peer-vetted credibility—visibility that feels “earned” rather than self-declared.

Different channels. Different strategies. Same underlying goal: be seen without being penalized.

What leaders get wrong about recognition

Most leaders think recognition is a nice-to-have. A morale booster. A cultural perk.

But recognition is also an information system. It’s how organizations decide what “good” looks like, who is progressing, and whose work counts.

If self-promotion feels unsafe, recognition becomes distorted. The organization doesn’t just miss out on feel-good moments—it misses data about performance, impact, and potential.

And in that vacuum, perception rushes in.

When recognition reflects comfort rather than contribution, the people who feel safest speaking up become overrepresented in the narrative of success.

That’s not just unfair. It’s operationally expensive.

How to build a culture where wins can breathe

This is the part leaders can control—without telling employees to simply “be more confident.”

1) Make recognition a system, not a personality contest

If celebrating wins relies on who speaks the loudest, you don’t have a recognition culture—you have a visibility contest.

Build rituals where sharing impact is expected and normalized:

- “Win of the week” moments in team meetings (with prompts that focus on outcomes)

- Post-project retros that include a recognition round

- Rotating “impact spotlight” where peers nominate one another

The key: shift recognition from optional to routine.

2) Train managers to be amplifiers, not just evaluators

Because encouragement matters almost as much as confidence, managers are the lever.

Give managers simple scripts and habits:

- “I want you to share that outcome in tomorrow’s meeting—I’ll back you up.”

- “Can I highlight your work in the leadership update? Here’s what I’ll say—does this feel accurate?”

- “Let’s document this impact so it’s visible during performance conversations.”

In healthy cultures, managers don’t wait for employees to self-advocate perfectly. They help translate work into visibility.

3) Create safer formats for visibility

Not everyone wants a spotlight. That doesn’t mean they don’t want growth.

Offer multiple ways to share achievements:

- Small-group settings

- Written updates

- Peer nominations

- Structured prompts (what you did / why it mattered / what you learned)

The goal isn’t to force one style of self-promotion. It’s to reduce the social risk of being seen.

4) Don’t outsource the problem to “personal branding”

One of the more revealing findings: personal branding training was a top-three factor helping women feel more comfortable self-promoting—but it didn’t make the top three for men.

That can easily be misread as “women need training.”

A better interpretation: women are trying to find safer language for visibility in cultures that punish the wrong kind of visibility.

So yes—training can help. But if training is your main intervention, you’re treating the symptom, not the system.

The simplest takeaway

Employees aren’t lacking confidence in their achievements.

What holds many of them back is how workplace culture interprets—and sometimes penalizes—self-promotion.

And once you see self-promotion as a cultural behavior rather than an individual trait, the solutions shift. You stop asking people to be braver inside the same environment. You start shaping an environment where being visible doesn’t come with hidden costs.

That’s when recognition stops being a performance.

And starts being a reflection of performance.

%20(1).png)

.avif)

.avif)